National headlines carried the news in the summer of 1953: 41-year-old Winthrop Rockefeller, fourth son of one of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful families and a dashing society figure, had suddenly pulled up stakes from New York City and relocated to the top of a mountain in the middle of Arkansas.

Early Life

Of course, the only thing about the move that should have come as much of a surprise was the destination. In fact, it was the third time Rockefeller had veered off the course that his family — and the country, for that matter — expected him to take toward a cultivated lifestyle in New York and leadership of one of the family’s enterprises.

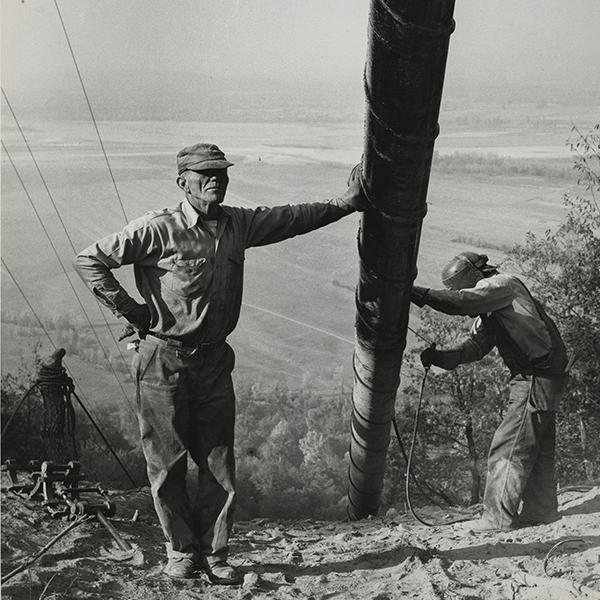

First, he left Yale during his junior year to work as a roughneck in the dangerous Texas oilfields of the 1930s, where he made 75 cents an hour and lived in a rented room for $4.50 a week. Then, after finally accepting a position in one of the family’s companies in 1937, he quit in 1941, enlisted in the Army as a private, completed Officer Candidate School, and fought as an infantry commander in the Pacific during World War II, earning a Bronze Star with Oak Leaf Clusters and a Purple Heart for his actions aboard a troopship attacked by a kamikaze pilot during the invasion of Okinawa.

The recurring theme that should probably have been apparent by 1953, when Rockefeller traveled to Arkansas at the invitation of an old friend from his Army days, was a desire to be in the thick of things, to do the hard, front-line work, to drill the wells instead of running the oil company, to fight the battles instead of helping finance the war effort.

Becoming an Arkansan

The 927-acre spread he bought atop Petit Jean Mountain provided ample opportunities to do exactly that. Rockefeller promptly set about turning the half-wild sprawl into a model cattle farm, pumping water 850 feet up the mountainside from the Arkansas River below; building lakes, roads, and an airstrip; and building and rebuilding structure after structure.

But he soon learned that the need for change didn’t end at the borders of his property. At the time, Arkansas was mired in what Time magazine called a “dead-end economic and political condition.” Jobs were few, wages were low, the schools were poor, and health and dental care were hard to come by. A one-party political system, plagued by persistent corruption, didn’t help.

In this situation, Rockefeller found what he had looked for all his life: a worthy challenge. He threw himself into the task of improving the quality of life in Arkansas with feverish energy and purpose, spending not only vast amounts of energy, but also vast amounts of his personal fortune. “Win found himself in Arkansas,” his brother Nelson, at the time governor of New York, said later. His brother David, president of Chase Manhattan, said, “It was just what he wanted and needed.”

With the means and the freedom to live virtually anywhere in the world he wished and to do virtually anything that struck his fancy — including enjoying a life of luxury and privilege — Rockefeller chose to put down roots in Arkansas, which at the time had arguably the lowest standard of living in the United States, and devote himself completely to making it a better place.

A Two-Party System

Those efforts started in earnest in 1955, when Gov. Orval Faubus appointed Rockefeller head of the newly established Arkansas Industrial Development Commission. During his nine years as chair of the AIDC, some 600 new industries came to Arkansas, providing 90,000 jobs and paying an annual $270 million.

Of course, Rockefeller also injected a great deal of his own capital into the state’s economy, staying true to a family tradition of sweeping philanthropy. He financed a model school in Morrilton at the foot of Petit Jean, led efforts to create the Arkansas Arts Center in Little Rock, paid for new health clinics in rural areas, and supported the state’s universities, ultimately giving well in excess of $10 million.

But his work to reform the state’s de facto one-party political system would prove to have broader impact in the end than either his philanthropy or his work with the AIDC. Rockefeller, according to a 1966 Time article, “served as financier, architect and mason of a two-party system more promising than any in the South,” succeeding “almost singlehanded in renovating [Arkansas’] political structure.”

Despite this campaign to bring the stereotypical smoke-filled rooms where much of Arkansas politics took place out into the daylight, Rockefeller had never had political ambitions of his own. But by 1964 it had become clear to him that if he was going to effect the kind of change he believed Arkansans wanted and needed, he would have to run for governor. That year, he was defeated by Faubus but won 44 percent of the vote, twice as many as any Republican candidate since Reconstruction.

Our 37th Governor

Two years later, against Jim Johnson, Rockefeller won, carrying 54 percent of the vote and some 80 percent of the Black vote. The state’s House of Representatives was still made up of 97 Democrats and three Republicans, and all 35 state senators were Democrats. But Rockefeller’s governorship was still a turning point of historical proportions.

Pragmatic and egalitarian, Rockefeller rejected the segregationist fervor of the era (his opponent had openly refused to shake hands with Black voters) and instead focused on education, economic progress, infrastructure and government reform. That the state of Arkansas sided with him and against a damaging but deeply entrenched status quo changed the tenor of politics across the nation.

Rockefeller served two consecutive two-year terms as governor, pursuing his agenda of reform and progress. Throughout that time, he continued to operate his farm, which by the time of his first election in 1966 comprised not just the Petit Jean property but some 34,000 acres and 6,000 head of cattle spread across three states. He also continued to conduct business — farming, philanthropy and governing — from his beloved mountaintop estate.

The Legacy of a Catalyst

The impact of Winthrop Rockefeller’s life can easily be seen in Arkansas. Various institutions bear his name and/or were spawned by his philanthropy and vision. After Rockefeller’s death in 1973, his only son, Winthrop P. Rockefeller, carried forward the governor’s ideals. The younger Win Rockefeller served as the state’s lieutenant governor from 1996 until his untimely death in 2006, showing throughout his time in office the same resolve and commitment to a better Arkansas that defined his father’s legacy.

That legacy of leadership was marked most notably by Winthrop Rockefeller’s understanding of the importance of collaboration, his ready acceptance that the problems facing the state he had grown to love could never come from him alone. Famously, during the 20 years he lived on Petit Jean, he convened more than 200 formal and informal discussions among business, political and thought leaders to hammer out solutions to a huge variety of issues.

And that — bringing the right people together in the right ways in order for them to see what needed to be done and do it themselves — was what Rockefeller wanted most to be remembered for. Despite his philanthropy, his business enterprises, his political accomplishments, he was most proud of what he inspired others to do. Upon leaving office, he said he hoped his legacy would be that of “a catalyst who hopefully served to excite in the hearts and minds of our people a desire to shape our own destiny.”

Today, the Winthrop Rockefeller Institute strives to perpetuate that legacy by continuing the tradition of convening great thinkers and leaders here at Rockefeller’s historic estate to work collaboratively on solutions to issues and problems facing Arkansas, our country and our world.