by Janet Harris

When she was 23 years old, Marion Stevenson walked into the offices of Governor Winthrop Rockefeller to apply for a position as a secretary in his administration. She’d been turned down for the job in two previous interviews with Everett Fulgham, an aide to Rockefeller, who had told her she was too young and didn’t have enough experience. Undaunted, she tried a third time, only to be told no.

Then a curious thing happened. A couple of weeks later, out of the blue, Fulgham called Stevenson to offer her the job. “I told the Governor about you,” Fulgham said. “He told me we needed to go ahead and hire you because you weren’t going away.” More than fifty years later, Stevenson credits Fulgham for sharing the story of her persistence with the Governor and says looking back now, she understands why her determination impressed him.

“He approached everything like that,” Stevenson said, speaking of Rockefeller’s dogged determination never to give up. “I didn’t know it at the time, but my persistence in continuing to go back, I think, took him back maybe to how many times he was challenged and just dug in.”

Marion Stevenson

Former Executive Secretary to Winthrop Rockefeller“He had a vision for the state, he had a vision for our government, he had a vision for the Republican Party, and he wasn’t going to allow ‘the little things’ to get in the way.”

Rockefeller’s resolve to persevere despite the obstacles showed up repeatedly throughout his life. Anyone who has participated in a program at the Winthrop Rockefeller Institute has likely heard about the Governor’s favorite poem, one that he carved into a piece of plywood by harnessing rays of sunlight with a flashlight lens. The poem, called “It Couldn’t Be Done” by Edgar Guest, gives us powerful insight into Winthrop Rockefeller’s philosophy about overcoming obstacles and seeing possibilities where others could not.

Somebody said that it couldn’t be done

but he with a chuckle replied,

that maybe it couldn’t

but he would be one

who wouldn’t say so ’til he’d tried.

So he buckled right in with the trace

of a grin on his face

and if he was worried, he hid it.

He started to sing, as he tackled the thing

that couldn’t be done

and he did it.

Serving at the Winthrop Rockefeller Institute, which is charged with helping to perpetuate Winthrop Rockefeller’s legacy, I think about this poem a lot. Our mission of collaboration across divides is occasionally met with cynicism from people weary of our polarized politics. Asking people to see the humanity in someone they disagree with or putting aside individual agendas for the sake of the collective good feels out of reach for many – as distant in our history as Winthrop Rockefeller himself.

To understand how we might “buckle right in with the trace of a grin on our face” to enable collaboration despite these odds, another bit of Winthrop Rockefeller’s legacy is essential to know.

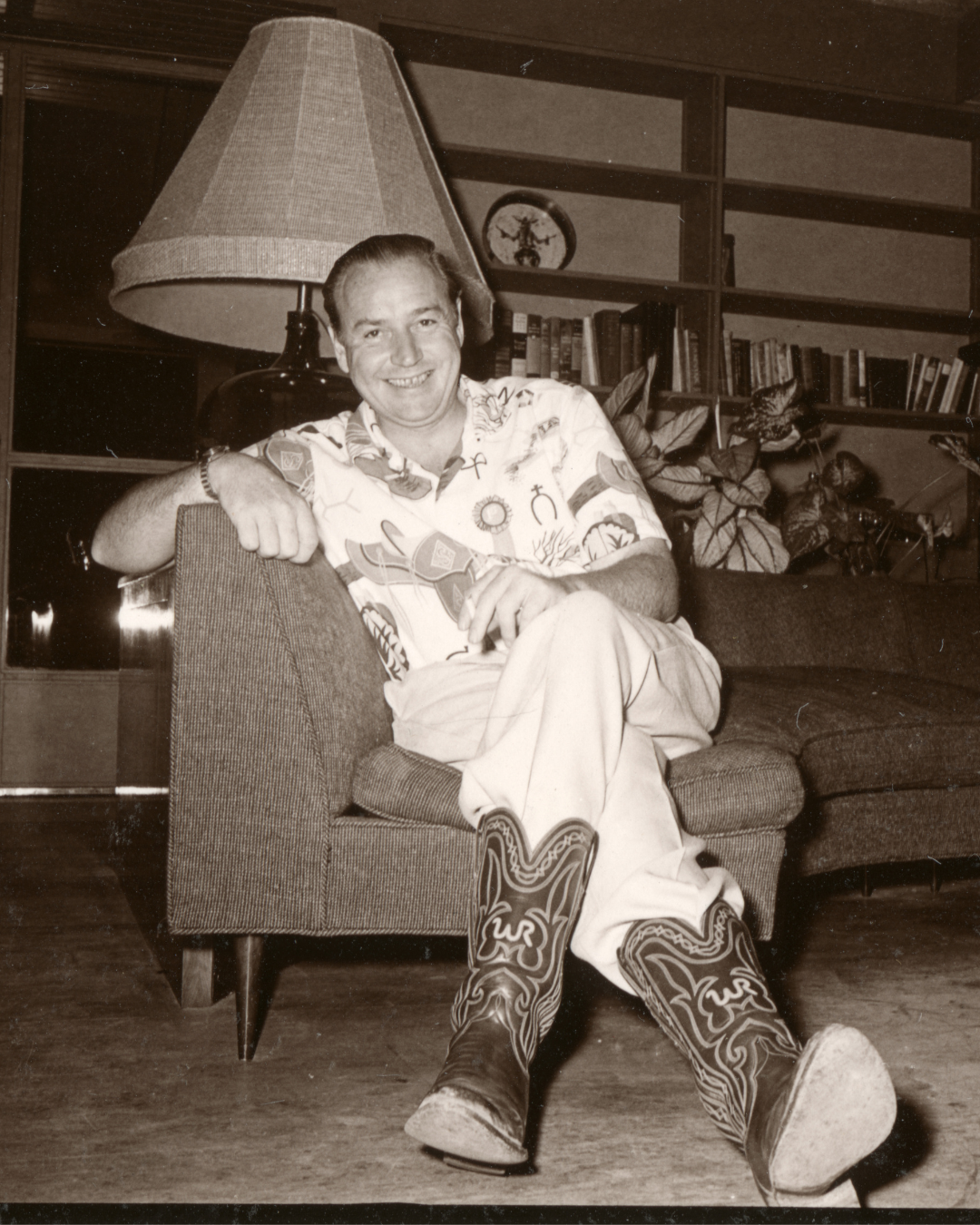

He was a determined man, yes. Resolved to make his own way in the world, he took the road less traveled in his academic studies, his early career as a roughneck in the oil fields, his service in World War II as an enlisted man, and finally, surprisingly, as a mountaintop cattle farmer and the first Republican governor since Reconstruction in the Democrat stronghold of Arkansas. His determination was rooted in a purpose — his deep love for humanity.

Winthrop Rockefeller’s heart for people was influenced by his mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, who emphasized the importance of extending respect to everyone around her and who would once caution her children “…never to say or do anything that would wound the feelings or the self-respect of any human being and to give special consideration to all who are in any way repressed.”

Beyond this love of humanity, both Winthrop’s mother and father instilled in him and his siblings the idea that they had a responsibility to give back to the world and to make it a better place for the people who lived in it.

Winthrop gave back through the relationships he built with people and the respect and mutual understanding he tried to build with those around him, especially those with whom he disagreed. In his time on Petit Jean Mountain, he repeatedly called together those who had a stake in solving our biggest problems and encouraged them to find a way forward. He extended his own personal hospitality to make people feel at home and took time to be curious about how to lift up his adopted state and the people he had grown to love who lived here.

Fifty years after his death, the Institute continues to invite people to connect with one another, collaborate across divides, and “create new solutions to old problems,” as Winthrop Rockefeller challenged us to do. We anchor our process in bringing diverse viewpoints to the table, pushing for respectful but hard conversations, and collaborating for transformational change. We call this process the Rockefeller Ethic.

Marion Stevenson shared her memories of Governor Rockefeller with our staff and me on several occasions last Fall. On the fiftieth anniversary of Winthrop Rockefeller’s passing, it seems fitting to remember his influence on so many people and celebrate the man’s heart.

Stevenson would go on to work closely with Winthrop Rockefeller until his death in 1973. She is now retired and living in Little Rock with her husband, Redding, who also worked for Rockefeller. The two were married during Rockefeller’s 1968 re-election for governor. Stevenson spent many years on Rockefeller’s personal staff, in the end working as his executive secretary.

Revisiting his outsized influence on her family’s life, Stevenson explained that “there is the love you have for someone who touches your life and changes who you thought you were and makes you a better person. And for me, he did that…He was able to inspire us to follow his lead in all of the things that were important to him.”

Rockefeller’s determination and deep love for humanity were essential to him and are timeless components of his legacy. He saw it as our duty as citizens to work together. Working together across differences, trying hard to understand one another, and finding common ground may sometimes seem out of reach. That is the challenge we confront today in a world that Rockefeller would no longer recognize.

Yet despite the odds, Rockefeller’s legacy fifty years after his death insists that we never stop trying.

He honestly left a legacy here in our state. Too bad that the likes of him in others seems to have disappeared. Would that it could resonate again. Please keep trying.

Great article!